Amy King, VIDA Chair Executive Committee

Read MoreSearching for the Perfect Social Justice Poem?

Sarah Browning, Executive Director, Split This Rock

Sarah Browning, Executive Director, Split This Rock

Many people know Split This Rock for its bi-annual poetry festival held in even-numbered years in Washington, DC, but another valuable resource from the organization is The Quarry, a Social Justice Poetry Database. The over 300 poems in the database were originally published in Split This Rock’s Poem of the Week series, or were winners of Split This Rock’s annual poetry contest or the Abortion Rights Poetry Contest, co-sponsored by the Abortion Care Network.

The database is extremely easy to use with a list of ideas for possible uses for the data base that includes: find a poem to read as part of a meeting, demonstration or rally; take poems into classrooms to enhance curricula; provoke discussion; inspire your own writing; find a poet to give a reading; and of course, personal enjoyment.

The database can be searched by poet, poem title, key word or theme. Search tips on the site suggest starting with theme. Other options include format, geography and poet identity. My own searches for “guns” “hunger” and “peace each brought up a plethora of appropriate results.

Appropriate poems are not only easy to find but the site also provides the format for properly referencing the poems in MLA, APA, and Chicago styles thanks to the Purdue Online Writing Lab.

Split This Rock sends subscribers the poem of the week as part of its free newsletter. Learn more about Split This Rock from our recent Poetry Spoken Here podcast interview with Sarah Browning, Executive Director of Split This Rock.

Bunkong Tuon: Poetry and the Outsider

Charles Bukowski

Charles Bukowski

One of the important results of reading poetry is self-reflection and self-understanding. Poems tell us about human experiences and we compare them to our own. Sometimes an experience is wildly different from our own and we wonder how we’d respond to the unfamiliar situation. Other times it’s similar to our own and gives us a flash of recognition, a feeling like “hey, I’ve been there,” or “yes, that’s how it is” or “I’m not the only one who feels that way.”

Bunkong “BK” Tuon had that flash-of-recognition experience when he serendipitously came upon the poetry of Charles Bukowski. At the time he was working as a janitor after dropping out of community college. While visiting the library he happened into the poetry section and a book by Bukowski. Reading the poems, he immediately recognized Bukowski as a fellow outsider. As a Cambodian-American who had come to the U.S. as a child, he could relate to that outsider point of view. It was exactly the way he felt when he had been immersed in new and different culture. As BK describes it, it was like being irrelevant, on the sidelines, invisible. Reading Bukowski, led him to understand that he was not alone in his feelings and that his own outsider views were something that could be written about. That book changed his life. His interest in poetry increased and he ultimately pursued a career in literature.

It’s impossible for anyone who has not had the experience, to fully understand the depth of outsider-ness felt by new immigrants. In an earlier Poetry Spoken Here podcast, Gregorio Gomez, who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico many years ago talked about why he signs his Facebook posts as “the ghost who walks.” When asked where that came from, he said it was from his early days in the U.S. when he felt that he was invisible. Like BK, he felt like a ghost that people didn’t even know existed.

Juan Felipe Herrera: Poet Laureate / Performance Poet

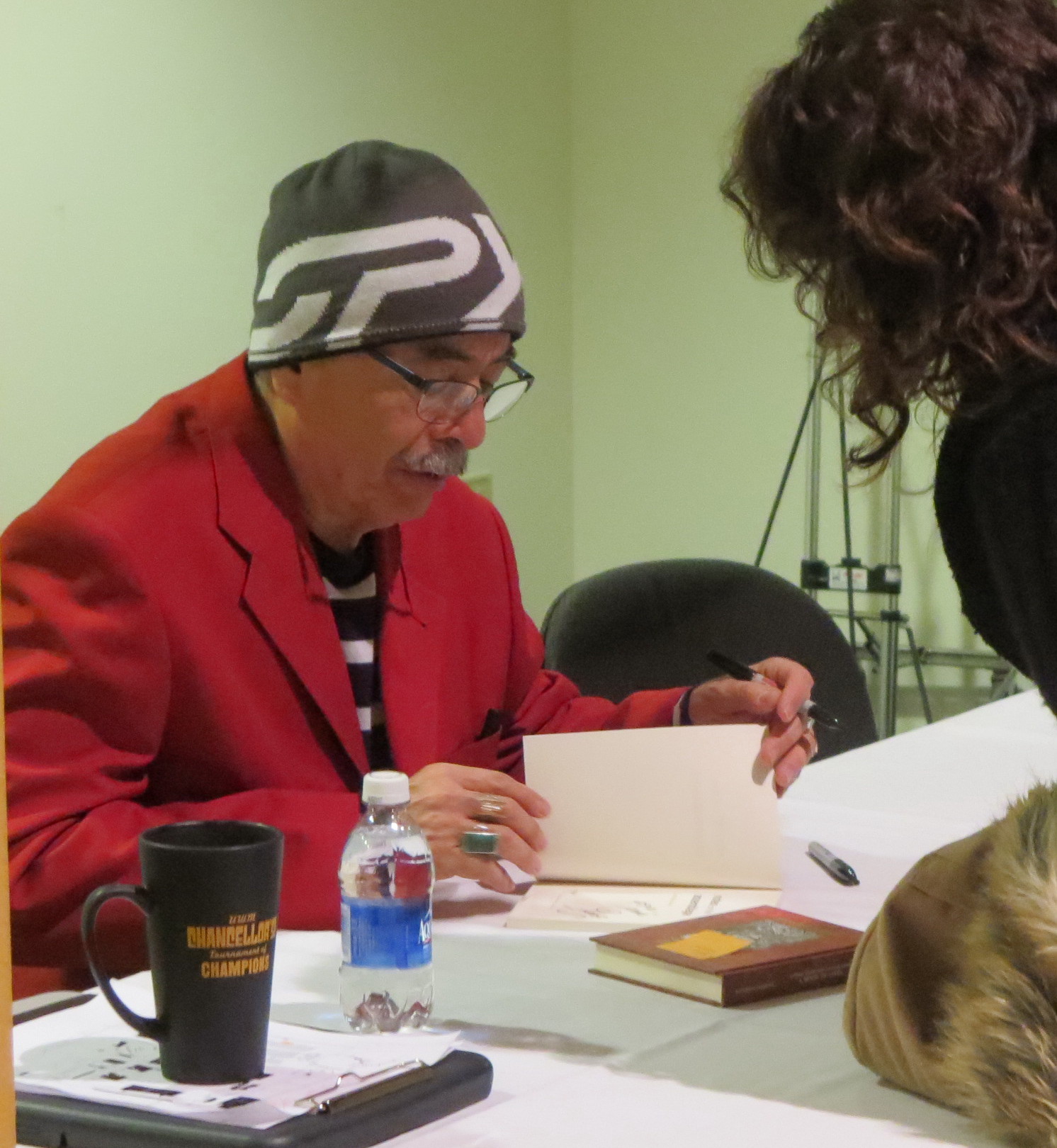

Juan Felipe Herrera, current Poet Laureate of the United States, signing book in Wisconsin.

Juan Felipe Herrera, current Poet Laureate of the United States, signing book in Wisconsin.

Juan Felipe Herrera packed the house for a reading at UW-Milwaukee’s, Union Ballroom, on Thursday, March 3rd. During the hour-long reading, Herrera showed that he has everything you could want in a major ambassador for poetry. He’s personable, humane, entertaining and a formidable poet.

After a brief introduction, Herrera came on wearing a bright red sport coat over a black horizontal-striped t-shirt with a bold patterned skull cap. (The hat was quickly discarded.) Herrera exudes a warm, positive vibe, sprinkling the readings with personal stories such as the one about when he traveled to Chiapas with a supply of beads and machetes, presumably to trade with the locals, because a guide book for anthropologists suggested he do so. Once he actually met the locals, he was chagrined to realize that advice from a book written in the 1940s has become completely useless.

Herrera deserves high marks for presentation. He’s the only poet laureate I know of who skillfully uses performance poetry techniques to get his poems across. He used call-and-response to get the audience chanting “climate change” with him; at another point he sang-talked a portion of a poem, and later he even danced a little. He even had the audience speaking Spanish during another call-response.

It’s heartening to hear a poet laureate who is willing to address contemporary issues such as the use of excessive force by law enforcement. His belief in the relevance of poetry is evident in one of his most powerful poems, written for those slaughtered in Charleston. It begins “Poem by poem we can end the violence.”

The reading culminated with a standing ovation followed by an encore of three short poems. Needless to say, if the poet laureate gives a reading in your town, you’ll want to hear him, but get there early—the official attendance count for this reading was 650.

(NOTE: Herrera will be reading Friday, April 13, at the Library of Congress as a kick-off event for this year’s Split This Rock poetry festival in Washington, D.C. There’s a conference fee, but Herrera’s reading is free and open to the public.)

The Performance Poetry Preservation Project: A Growing Archive of Poetry History

Wess Mongo Jolley, President of P4

Wess Mongo Jolley, President of P4

According to their website that has recently gone live, The Performance Poetry Preservation Project (P4) is the only community-supported, grass-roots effort that protects and preserves the recorded history of the poetry slam movement. P4 has begun development of a carefully curated performance poetry archive, designed to document the slam poetry movement.

With so much poetry being recorded these days, the importance of 4P might not be obvious, but as they point out, simply recording an event is not enough. As they note: “Without proper storage, care and stewardship, many of these recordings will simply become unreadable in as little as five to ten years. The media will deteriorate, formats will change, or they will simply be discarded due to a lack of a repository to properly preserve them. Simply put, that stack of CDs on the Slammaster’s shelf will one day be as useless as a drawer full of computer punch cards or a box of 5 ¼ inch floppy disks. A whole generation of poetry history and performance is in danger of being lost.”

Fortunately, the volunteers at P4 are not a bunch of wild-eyed dreamers. They’re a pragmatic group with real years of professional experience in the field. They’re not just building an archive, they’re building it right.

As the collection grows, it will continue to give top priority to material from the first 25 years of the slam, 1987-2012. The collection also hopes to include recordings after 2012, and from before 1987, if the material has a “meaningful influence on the development of the slam.”

Contributions of slam media are welcomed, and 4P will reimburse donors for USPS Priority Mail postage. However, it’s important to first check their website for 4P guidelines and procedures for making donations. To learn more about the Performance Poetry Preservation Project, listen to our podcast interview with Wess Mongo Jolley, the organization’s president.

Writing Haiku: Lee Gurga's "Haiku: A Poet's Guide"

Lee Gurga, author of Haiku: A Poet's Guide

Lee Gurga, author of Haiku: A Poet's Guide

If you’ve spent any time at all investigating the nuances of English language haiku, you have no doubt run into the issue of whether of not to count syllables. Some adhere to the idea that haiku is a 3-line form with 5-7 and 5 syllables in the three lines. Others argue that the syllable count doesn’t make the kind of sense in English that it makes when writing in Japanese.

The non-syllable counters point out that it’s not the number of lines and syllables that define haiku but rather whether or not the poem adheres to haiku principles. They argue that a good haiku must reflect the immediacy of a specific haiku moment. Furthermore, a good haiku will juxtapose two images that when presented together make up a whole that is more and different than the sum of its two parts.

There’s no reason to expect syllable counting to go away. Teachers like to teach syllable-counting haiku. Emphasis on syllable counting means that they can give students easy to define assignments. That’s a lot simpler than attempting to explain the essence of a haiku moment and the idea of evoking a feeling by presenting two juxtaposed images. Randy Brooks elaborates on the defining characteristics in his appearance on the Poetry Spoken Here podcast.

If you are interested in going beyond physical form and learning about the true essence of haiku, Lee Gurga’s book, Haiku: A Poet’s Guide is a great resource. Gurga not only explains the elements of haiku, but he also warns against common pitfalls such as trying to tell too much of a story or cramming too many images into a single haiku. A unique benefit of this book is that he illustrates his points with examples of poorly written haiku. You may think that qualitative judgments in poetry are a matter of opinion, but when you read the examples he provides you’ll find it easy to understand why he considers some excellent and others deficient.

You may also be interested in looking into the Haiku Society of America, a source of ongoing encouragement and support for haiku writers.

To hear Randy Brooks discuss haiku at length on Poetry Spoken Here, click here.

Ted Kooser's New Book of Metaphor-Rich Prose Poems

The Wheeling Year is a bit different for Ted Kooser. The University of Nebraska Press classifies the book as “memoir/creative nonfiction,” but it reads and feels like a collection of prose poems.

Kooser’s poetry is in some ways similar to the poems of the ancient Chinese. At first glance, he appears to present a straightforward description of every scenes and experiences. Upon closer examination it’s clear there’s a lot going on beyond mere description. It all begins with close observation that Kooser values so highly. As he notes, “it is all around us, free, this wonderful life. . .each hour is a gift to those who take it up.”

An important reason for the poetic feeling to these pieces lies in Kooser’s extensive and effective use of metaphor. In one poem the rain is “a woman with thin old hands” that she uses to rearrange the leaves, until they are positioned in a way that pleases her. In another, sunflowers in a field become troops in their uniforms, “little more than a few mildewed tatters of khaki and brown” in front of their “cold gray barracks of late autumn dawn.” A catalog of his grandmother’s kitchen items is compared to a birder’s life list of items such as her iron skillet with its low scrape of song, and the chirping percolator (but not the Cuisinart or Salad Shooter). In his characteristic manner, Kooser conveys the basic information and his points get made, but always in a highly poetic way.

In the preface, Kooser likens the book to the field books of a landscape painter friend who uses them for sketches and observations of daily life. There is a journal-like feel to The Wheeling Year, with the entries presented in chapters named for the months of the year. It’s worth noting that, like his publisher, Kooser does not claim to have written a collection of prose poems. On the other hand, the pieces are too polished to be casual observations noted down in the field, even for a poet laureate with Kooser’s considerable talent.

The U of N Press kindly provides a sampling.